The recently leaked document provides new insight into how China characterizes extremist threats.

More than three quarters of the names on a recently leaked Chinese government list of some 10,000 “suspected terrorists” are ethnic Uyghurs, while the document includes hundreds of minors and the elderly, providing rare insight into how Beijing characterizes threats it has used to lock up more than a million people.

In 2020, a group of Australian hackers obtained the list, which was culled from more than 1 million surveillance records compiled by the Shanghai Public Security Bureau “Technology Division” and, after vetting it for authenticity, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) published it last month.

The PSB unit is responsible for building databases and “image, wireless, and wired communication systems,” according to ABC, and experts say it most likely determines who should be placed on watchlists and further investigated as potential threats to the state.

Most of the entries on the document, which RFA’s Uyghur Service has obtained a copy of and refers to as the “Shanghai List,” include dates of birth, places of residence, ID numbers, ethnicity, and gender of the individuals, nearly all of whom are referred to as “suspected terrorists,” although some are identified as having “created disturbances.” More than 7,600 of the people listed on the document are ethnic Uyghurs, while the rest are mostly Kazakh and Kyrgyz, fellow Turkic Muslims.

The list, which analysts believe was compiled in 2018 at the latest, contains entries for individuals from all walks of life in Uyghur society, including ordinary citizens, children as young as five and six years old, senior citizens in their 80s, and Uyghurs who have lived and traveled abroad, as well as Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) who have never been abroad before.

More than 400 minors are identified on the list as “terrorist suspects,” 162 of whom are under the age of five. The document says that children as young as five have been “met and examined” by security personnel.

The Shanghai List gives no evidence or explanation as to why the listed individuals are suspected of terrorism, although many of the adults appear to be individuals of social influence and successful in their various fields of work, or have been vocal about ongoing abuses in the XUAR in the diaspora.

RFA has so far located multiple people living in the U.S. and identified several others who are on the Shanghai List, including Abduqeyum Hoja, the 81-year-old veteran archaeologist and father of RFA reporter Gulchehra Hoja, who the Chinese government has previously accused being a terrorist.

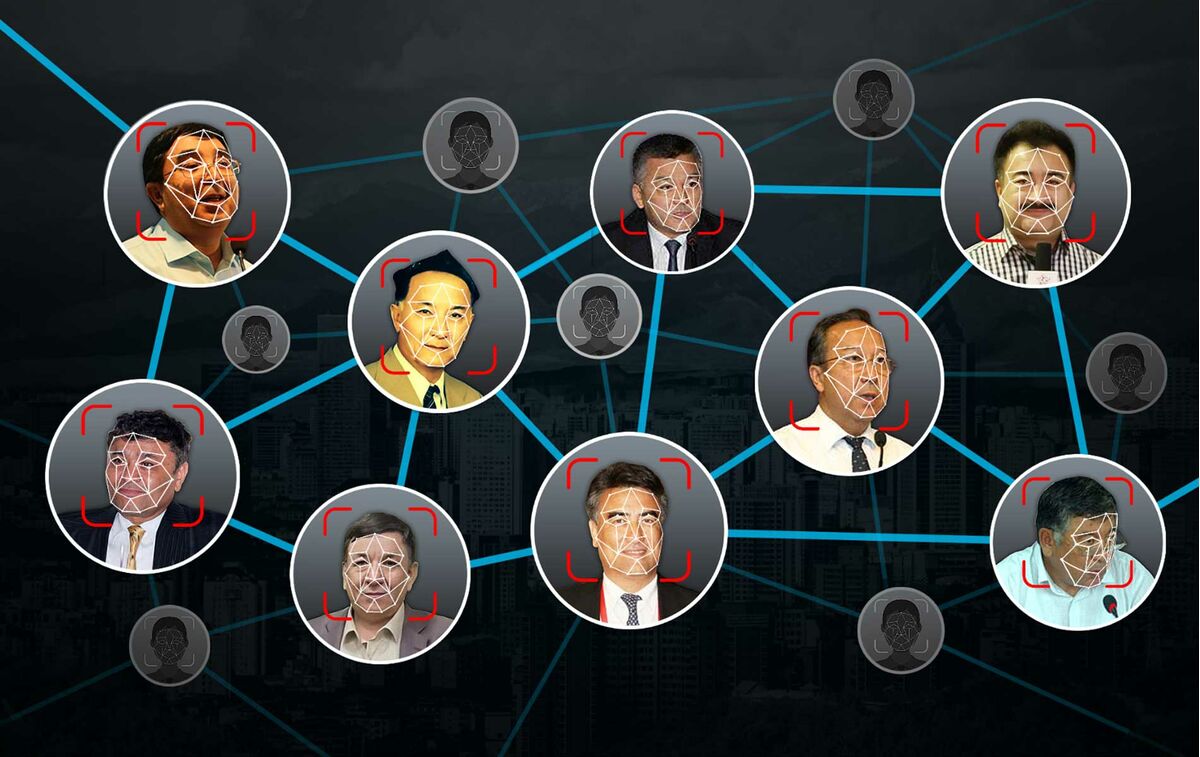

The list also contains entries for the former heads of universities in the XUAR, including Tashpolat Teyip, Halmurat Ghopur, Azad Sultan, and Wali Barat; writers, poets, and publishers including Yasin Zilal and Abdurahman Abay; famous musicians and artists such as Adil Mijit, Hurshide Turdi, Abdurahman Ayup, Jurat Wayit, and Gulzar; and even children named Atilla Tursun and Akida, who were born in 2014 and are at most seven years old.

Learning about inclusion

A Uyghur truck driver based in Virginia, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal because his family members remain in the XUAR capital Urumqi, told RFA that he had heard he was on the list, although he had not seen it for himself.

“Initially I was surprised, but … given that I’ve been separated from my wife and children, [the list] just seems like a rather small matter,” he said, adding that he is unsure why he may have been targeted.

Another Uyghur named Bugra Arkin told RFA he is not on the list, despite living abroad, but that his Urumqi-based parents and younger sister are. He said his family’s publishing house, which was opened in 2007 with the goal of “enriching Uyghur cultural life,” has been shut down and that four employees had been detained along with his father.

“I know something like 20 or 30 people on the list” from a residential area around Urumqi’s Xinjiang University, he said.

Shawkat Abdulla, a 59-year-old father of four, is a Uyghur farmer who has been living in Turkey with 17 of his family members, including his children and grandchildren, since 2016. Like thousands of Uyghurs abroad, Abdulla and his family came to Turkey seeking safety and security.

While working to build a new life in a foreign land, Abdulla said the last thing he expected was to find himself on a list of suspected terrorists after reading a post about “fugitives” on Facebook.

“When I looked into it, I saw my own name there, with my address. I wondered what was going on, and when I told a buddy of mine about it, he told me that [someone in] Australia had found and published the Shanghai List,” he said.

“At first, I was worried, but then I said to myself, ‘We shall see what Allah will bring us. This isn’t happening only to me, there are 8,000 [other] people,’ and I found some comfort. But at first, I was a little scared. I was truly worried.”

The leak of the Shanghai List comes as a campaign of extralegal mass incarceration enters its fourth year in the XUAR, where authorities are believed to have held up to 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in a vast network of internment camps since 2017.

While Beijing initially denied the existence of the camps, China in 2019 changed tack and began describing the facilities as “boarding schools” that provide vocational training for Uyghurs, discourage radicalization, and help protect the country from terrorism.

But reporting by RFA and other media outlets indicate that those in the camps are detained against their will and subjected to political indoctrination, routinely face rough treatment at the hands of their overseers and endure poor diets and unhygienic conditions in the often-overcrowded facilities. Former detainees have also described being subjected to torture, rape, sterilization, and other abuses while in custody.

Amid increasing scrutiny of China’s policies in the XUAR, the U.S. government in January designated abuses in the region part of a campaign of genocide — a label that was similarly applied by the parliaments of Canada, The Netherlands, and the U.K.

Defining ‘terrorism’

Analysts and observers told RFA the Shanghai List is testament to just how vague and widespread the concept of “terrorism” is in China, and how the government is abusing this concept as a pretext for repressing Uyghurs.

Netherlands-based Asiye Abdulahad, who also goes by the name Asiye Uyghur, said it is “impossible” for there to be so many “terrorists” in the XUAR at this time given the reality of the on-the-ground situation over the past few years.

“When we look at the large number of Uyghurs who have been accused of crimes and detained, and when we look at the fact that they’re in no hurry to differentiate between old Uyghurs and young Uyghurs before putting them on a terrorist list, we can infer here that the detention of Uyghurs is very widespread,” she said.

“It’s simply not possible that there is the risk of there being any such people in the homeland right now, because the restrictions there, the restrictions they’ve put on Uyghurs for all kinds of things, are so great in number.”

Instead, she said, putting so many people — including children — on a list of suspected terrorists suggests that “Uyghurs have been detained for the normal, everyday practices undertaken by Muslims all over the world, and for normal, everyday cultural practices.”

Adrian Zenz, a Senior Fellow at the Washington-based Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, who has mined Chinese government reports and statistics to help document the extent of the camp system, said the list sheds light on China’s treatment of Uyghurs, and noted that there is no evidence that any of these people have anything to do with terrorism.

“All kinds of Uyghurs have been turned into terrorism suspects, even if they have absolutely no connection at all, like they haven’t even been to China for years, or they're just business people, or … they are minors, including some children as young as five years old, people who have done absolutely nothing and that’s widely known,” he said.

“It shows sort of the arbitrary nature of Chinese designations, basically placing an entire people group under a blanket suspicion, without any distinction or differentiation. And that, I think, is very concerning because it just shows that there is the persecution of the Uyghur ethnic group as a group.”

Sean Roberts, director of George Washington University’s International Development Studies Program, told RFA he sees the Shanghai List as evidence of China’s intent to eradicate prominent people among the Uyghurs, and perhaps the Uyghurs as a people.

“Any signs of Uyghur dissent are to be suspected of terrorism or extremism or separatism,” he said.

“So even what we've seen in the last four years, even before you had people disappearing into mass internment centers, you had lots of people who were disappearing, and primarily from the intellectual class, including party officials.”

Roberts said the Shanghai List is part of Beijing’s narrative over the past four years that the Uyghurs as a people are a danger to the Chinese state.

“It gets into this idea of preventive policing that even people who have not done anything wrong, the Chinese government appears to view them as potentially a threat,” he said.

“[It’s the idea that] they may do something wrong, or they may do something that the Chinese government perceives as a threat to the state.”

Indiscriminate approach

Mehmet Tohti, director of the Uyghur Rights Advocacy Project in Ottawa, Canada, said that the composition of the list also suggests that Uyghurs were placed on it at random.

“There aren’t very many terrorist organizations in the world with more than 10,000 people on a list with ID numbers—the largest terrorist organizations only have several hundred people in them,” he said.

“If a country were really to be serious about figuring out how to deal with terrorism, and with finding out who was involved in terrorism, they would never just put people on a list like this. If nothing else, they would have to look at whether they’d done something, or whether they were planning something. So, this shows that the Chinese government has done this [put this list together] indiscriminately.”

According to Tohti, the list also shows how China has “purposely twisted and exploited this concept” of terrorism.

But he noted that the Shanghai List “is merely the one that people were able to get their hands on,” and wondered how many more exist like it.

“It’s possible that even larger numbers [of people] could become public tomorrow or the next day,” he said.

“If someone is simply Uyghur, whether newly born or a famous intellectual, it doesn’t matter what their identity is or what kind of person they actually are, they’re simply putting anyone whose information they can get onto [these lists].”

Reported by Jilil Kashgary for RFA’s Uyghur Service. Translated by the Uyghur Service. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/special/shanghai-list/